In days gone by–in other words, about a decade ago–an author could expect to have a given book run for a few years, if that long, and then disappear. The only exceptions were books that the publisher decided to make into bestsellers. Soon enough, though, the only place to find many books were used bookstores.

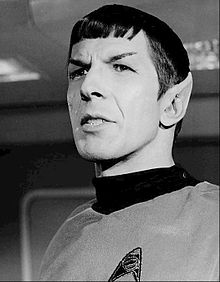

But now that these are widely available:

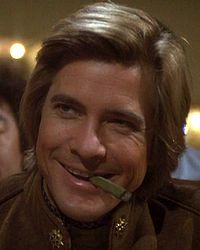

no, wait, I meant these:

and the like–yes, now that so many are carrying around devices that can store books by the thousands or even more, if they’re willing to have their books stored by someone else–someone who is making lists of everything you buy and read–where was I going with this?

Ah, the point I’m making is that now that books are widely available in digital form, there’s no reason for anything to go out of “print.” Books can be stored in hard drives for transfer at any time, and with print-on-demand becoming respectable, even paper copies can be cranked out whenever anybody wants one.

But with every new thing comes a new set of problems. In those days of auld lang syne, authors like Dan Brown and E. L. James mercifully disappeared after a momentary flash in the pan. But now, literary zombies can continue sucking the brains of their readers forever. Or am I talking about vampires? At any rate, mindless soul-sucking creatures that don’t die in the light, but glow a faint hue of sparkly and whose dialogue wouldn’t challenge the abilities of the New York telephone directory to thrill will be with us until we’re all living in Panem and don’t have time to read anyway. This means that every time readers go looking for a book, there will be many more than there were the last time.

So what’s an author to do? Leading a revolution to ban all books but the ones I write is one option. But that’s not likely to go over too well, especially since we authors are a cantankerous lot, and readers have the annoying habit of wanting a diversity of styles, genre, and subject matter.

Given the changes in technology and the field of publishing, I’ve reached the following conclusions:

1. Publishers must change or die.

Mene, mene, tekel, upharsin, as the writing on the wall declared. Publishers have been weighed in the balance and found wanting. They don’t promote books, except those by authors who are already famous. They are stuck in a world in which a book had to be handed from one person to the next, instead of being copied in an instant. Their business models treat books like boxes of cereal, when in fact books are today more like Internet memes.

2. Authors must produce quality work.

Yes, I know that lots of bad books get cranked out, many of them given away. But I hope that the reading public will come to its senses and realize that spending a little money for something that’s been well written and then edited is worth the expense.

3. Books must be promoted in new ways.

You can’t rely on putting ads in magazines and on librarians recommending your book. Eyeballs are on YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, blogs (such as this one with its many viewers like you), and other places that Charles Dickens never imagined when he sold novels in serial form. No one’s waiting at the docks for the next chapter to arrive from England.

But there is good news. The cost of all this digital publishing and marketing is low. Time and talent are the keys these days. So what’s the secret?

One thing is to exploit the fact that searching for what you want is as easy as putting something on-line. That is, searching is easy if the thing you want is tagged with enough terms that make finding it possible. If I want a book about the Sahara desert, yours just so happens to be about that, you’d better indicate that your book covers sand, the desert, the Sahara, Libya, Egypt, Algeria, Morocco, Mogambo, a guy named Dirk Pitt, and some rivers that have been dry a long time. No matter how tangential, tag it. Even throw in Dirk Benedict if you figure it will help.

Another thing is to get yourself on popular websites that allow comments with linking to more of you and make a name for yourself. I’ve found The Huffington Post to be a good place to practice this, especially since I can work in the occasional link to my blogs in what I say there.

Oh, but you want more, don’t you? Recall how I said it was cheap? That doesn’t mean free. I also said it takes time and talent, and that is for sale. My company, Oghma Creative Media, has a plan for you, a plan designed to make promotion successful and a whole lot easier.

Or you can just buy my books. That’s cheaper.

Crossposted on Greg Camp’s Weblog and Oghma Creative Media.